Acne vulgaris: A treatment update

Acne remains an unavoidable part of growing up for many adolescents, who must cope with both the cosmetic and psychosocial effects of the disorder. Here's a look at the latest topical and systemic treatment options for mild to moderate acne.

Cover story

Acne vulgaris: A treatment update

By Anthony J. Mancini, MD

Acne remains an unavoidable part of growing up for many adolescents, who must cope with both the cosmetic and psychosocial effects of the disorder. Here's a look at the latest topical and systemic treatment options for mild to moderate acne.

Acne vulgaris is probably the most common disorder of adolescence. It is estimated that up to 85% of individuals ages 12 to 24 years will get acne.1 Although it does not tend to be a serious disease, it may result in permanent scarring and disfigurement. More important, acne can have profound effects on psychosocial development and emotional well-being during a developmental period already marked by psychological turmoil. A recent survey of secondary school students in Auckland, New Zealand, revealed a direct correlation between acne severity and several social variables, including embarrassment and lack of enjoyment of (and participation in) social activities.2 In another study, surveys of 72 patients with noncystic (mild to moderate) facial acne revealed high scores for clinical depression on the Carroll Rating Scale for Depression, and a 5.6% prevalence of acute suicidal ideation.3 These studies highlight the importance of adequately treating acne, as the potential consequences of the disorder may reach far beyond its cosmetic impact.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reviewing this article the physician should be able to:

This review highlights the latest available therapies for mild to moderate acne vulgaris. It begins with a brief description of pathophysiology and acne lesion nomenclature since a thorough understanding of the clinical-pathologic correlation is useful in formulating a therapeutic approach. An account of the treatment strategies used with three hypothetical teenage acne patients concludes the discussion.

Pathogenesis and types of acne lesions

Acne vulgaris is multifactorial in origin. The pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to lesions usually begin with obstruction of the pilosebaceous (hair and sebaceous gland) units. These units are most numerous over the face, upper chest, and back, where there is sebuman oily, lipid-containing substance produced in increased amounts by sebaceous glands stimulated by elevated levels of circulating androgens.4 Sebum is produced in fairly high amounts after birth as a result of circulating maternal hormones. Production decreases as the glands eventually shrink, and the hormones are cleared from the circulation by about 6 to 12 months of age. Oil production again increases around 6 to 8 years under the influence of androgens and rises to peak levels during late adolescence.

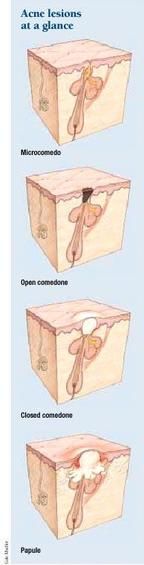

Another factor in the etiology of acne vulgaris is plugging of the pilosebaceous follicles. This plugging is related to disruption in the normal patterns of the epithelial cycle, with accumulation rather than desquamation of keratinized cells.1 The normal follicular duct becomes obstructed by the cell buildup and excess sebum, which form a horny plug. The first lesion to result clinically is the microcomedo, the precursor of all acne lesions. As the process continues, larger, noninflammatory lesions, comedones, develop. They may be open ("blackheads") or closed ("whiteheads"). The reason for the black appearance of open comedones is unclear, although compaction and oxidation of the keratinous material at the follicular orifice is one commonly accepted theory.

Propionibacterium acnes, an anaerobic resident bacterial organism, resides and proliferates in the lipid-rich mixture of sebum and keratinized cells within the pilosebaceous follicles.5,6 There is a direct correlation between density of colonization by this organism and the amount of lipid produced in the skin. Lipases liberated by P acnes hydrolyze sebum triglycerides into free fatty acids, which propagate the cycle of acne development by their comedogenic and proinflammatory effects. P acnes also secretes chemotactic factors, which attract neutrophils and other inflammatory cells to the site and may contribute to damage and rupture of the follicular wall.1,4 These infectious and inflammatory aspects of the acne cycle result in inflammatory lesions, including papules and pustules. With continued inflammation, macrophage recruitment and, eventually, foreign body reactions occur, leading to the larger lesions of cysts and nodules. Common sequelae of acne vulgaris include dyspigmentation and scarring. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may last for months to years, especially in individuals with dark complexions. Table 1 lists the various types of acne lesions.

TABLE 1

Types of acne lesions

Before initiating acne therapy, adequate patient education is a high priority. Important considerations include the need for compliance with therapy, the expected delay in noticeable improvement (up to four to eight weeks) inherent in any new regimen, and a thorough discussion of proper usage and dosing of medications and of potential side effects. Patient education materials, such as the guide for patients below, complement clinical interaction and increase compliance. They should be available in the office of every practitioner who treats patients with acne vulgaris. These materials can be created and personalized by the individual practice or purchased from national organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology (www.aad.org ) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (www.aap.org, or the Publications Department at 888-227-1770).

Topical therapies

Topical treatments alone may be effective in patients with mild to moderate acne vulgaris, especially when the condition is limited to the face. Such treatments are also a useful adjunct in patients who require systemic therapy. Several classes of topical preparations are available, each with a different mechanism of action. The main advantage of topical therapy is the avoidance of possible side effects associated with systemic agents. To maximize the potential for preventing acne, advise patients to apply topical agents as a thin layer over the entire affected region, rather than as "spot therapy" for individual lesions.

A variety of over-the-counter and prescription products are available for mild to moderate acne. Most OTC products contain either benzoyl peroxide (discussion to follow), glycolic acid, or salicylic acid. Glycolic acid is one of the alpha-hydroxy acids, which are carboxylic acids found in various natural products including fruits and yogurt. These agents decrease hyperkeratosis and may be useful in managing acne, although controlled studies are lacking. Salicylic acid is a keratolytic agent with drying and peeling effects that are especially useful for comedonal lesions, although its utility in preventing comedogenesis (new comedone formation) is more limited.6 It is available under a variety of trade names in 0.5% to 5% concentrations as a gel, lotion, wash, or cream.

Benzoyl peroxide (BPO) is the most frequently used topical preparation for the treatment of acne. BPO has antimicrobial effects to reduce colonization of P acnes on the skin surface, and has been shown to substantially decrease surface free-fatty-acid concentrations,7 which in turn may decrease the development of retention hyperkeratosis and microcomedones. It also has an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing the number of oxygen-free radicals. BPO is therefore active against both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions and may be useful as monotherapy for mild acne.

Benzoyl peroxide is available in concentrations of 2.5% to 10% and comes in a variety of formulations, including gels, lotions, washes, and creams. It is generally used once or twice daily. Skin irritation is one potential side effect, although it can usually be eliminated by gradually increasing the application frequency. Allergic contact sensitization has been demonstrated,8 although neither irritant or allergic reactions have significantly limited benzoyl peroxide's clinical use. BPO preparations can also bleach clothing.

Table 2 lists the various prescription benzoyl peroxide products available. Products that combine BPO and antibiotics, including erythromycin gel (Benzamycin) and sulfur lotion (Sulfoxyl), will be discussed in the section on topical antibiotics.

TABLE 2

Prescription benzoyl peroxide (BPO) products

Sulfoxyl regular

Topical retinoids are an extremely effective class of medication for the treatment of acne vulgaris, with strong comedolytic and anticomedogenic activity as well as indirect antibacterial effects.9 Tretinoin (all-trans-retinoic acid, Retin-A, Avita), an acid of vitamin A, is the prototype drug in this class and has been shown to normalize desquamation of the follicular epithelium, promote drainage of comedones, and inhibit new comedone formation.10 Tretinoin comes in cream, liquid, and gel formulations.

Newer topical retinoid or retinoid-like compounds include tazarotene and adapalene. Adapalene, a naphthoic acid derivative, has a retinoid-receptor specificity that may result in less irritation than other retinoids.1 In addition, a randomized, prospective, multicenter trial showed adapalene gel 0.1% to be significantly more effective and better tolerated than tretinoin gel 0.025%.11 Table 3 lists the topical retinoids currently available.

TABLE 3

Topical retinoids for acne

Topical retinoids are usually applied once daily, generally at night to decrease the risk of phototoxicity, a rare side effect. Adequate patient education is vital with these preparations, as incorrect usage and resultant side effects may be limiting and ultimately decrease compliance. The most common side effectserythema, dryness, and burningcan be minimized by instructing the patient to apply the medication only to thoroughly dried skin (at least 30 to 45 minutes of "air drying" following washing) and to apply the minimum amount necessary (a "pea-sized" amount is generally sufficient for the entire face). Liquid and gel forms of tretinoin tend to be more drying than cream forms.

The physician must play a role in minimizing the risk of these toxicities by prescribing the milder (low-strength) cream formulations to start, gradually increasing the concentration of the product as tolerated by the patient. Counsel all patients who are receiving topical retinoid therapy about the appropriate use of a sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 15 to 30 to avoid phototoxicity, the risk of which may be compounded by some of the systemic agents these patients may also be taking.

Given the known teratogenicity of systemic retinoids, the use of topical retinoids during pregnancy has been the source of much debate. There have been sporadic reports of congenital malformations associated with tretinoin, a pregnancy category C drug,12 although a controlled safety study in humans is lacking. The systemic availability after topical application is only 5% to 7%, and the risks for significant developmental fetal aberrations seem quite low.1315 Nonetheless, until a formal consensus exists regarding the use of these drugs in pregnancy, physicians should be familiar with the purported risks and discuss them with women of childbearing potential.

Topical antibiotics work by reducing the population of P acnes on the surface of skin and within the hair follicles.4 They may also have anti-inflammatory effects. The most commonly used topical antibiotics in acne therapy are clindamycin, erythromycin, and sulfonamides. Topical antibiotics do not have comedolytic effects and therefore are best used as part of a combination regimen for mixed inflammatory and comedonal acne. These agents are generally well tolerated and are usually applied to the affected areas once or twice daily. Table 4 lists topical antibiotics useful in the treatment of acne vulgaris.

TABLE 4

Topical antibiotics for acne

Topical clindamycin (1% phosphate) is available as a gel, solution, or lotion, and in pledgets. The solution and pledgets contain isopropyl alcohol and may cause drying in patients with dry or sensitive skin; this same effect may be attractive to patients with excessive sebum production. Since these formulations dry quickly, they are also the ones most compatible with the application of make-up.

Clindamycin lotion contains cetostearyl alcohol in a glycerin base and is usually well tolerated by most patients. There are rare case reports of pseudomembranous colitis following application of topical clindamycin, although in one such report the patient was using the hydrochloride salt, which is absorbed more than the phosphate salt.16,17 Nonetheless, any patient using topical clindamycin who develops persistent diarrhea should have stool studies for Clostridium difficile.18

Topical erythromycin is available as a solution, ointment, and gel, as well as in pads or pledgets. There is also a liquid preparation containing zinc acetate (Theramycin Z). The addition of zinc has been shown to result in reduced P acnes counts, decreased free fatty acids in surface lipids, and therapeutic efficacy similar to oral tetracycline.19,20 As with topical clindamycin, the alcohol-based formsin this case the solution, gel, and pledgetmay be more drying. In most patients, though, topical erythromycin is well tolerated and effective.

A combination gel of topical erythromycin and benzoyl peroxide (Benzamycin) is also available and has been found to be more effective than either component alone or the gel vehicle in a blinded, randomized trial.21 The product is applied once or twice daily and is well tolerated except for occasional irritation, dryness, and patient complaints of a "'white film" visible on the skin after application. It also requires refrigeration, which may be limiting in some clinical circumstances.

Sulfonamides are another class of topical antibiotic used to treat acne. The sulfonamide in these preparations is sodium sulfacetamide, and it is available in lotions both with and without 5% sulfur. Sulfur, an older therapeutic agent in dermatology, may be useful in treating acne vulgaris because of its keratolytic effects.22 Sulfacet-R is a topical sulfacetamide lotion that comes with a color blending tint, which can be titrated by the patient to match skin tone. It thus provides both a cosmetic cover-up and the therapeutic benefit of antibiotic treatment.

The most common complaint about topical sulfonamides is their smell. Reassure patients that the odor the product has when it is in the bottle becomes minimal to nonappreciable following topical application. Avoid prescribing topical sulfonamides in patients with known allergy to sulfa preparations.

Azelaic acid is a naturally occurring dicarboxylic acid produced by the fungal organsim Pityrosporum ovale with demonstrated activity against P acnes and the ability to decrease microcomedo formation. It also has the desirable effect of decreasing hyperpigmentation caused by acne. Azelaic acid may be effective as monotherapy in mild disease, and has been shown to be quite effective in conjunction with systemic antibiotic therapy for moderate to severe inflammatory acne.23 It is generally well tolerated except for mild tingling or erythema after application.9 It is marketed as Azelex 20% cream and is applied twice daily.

Systemic therapies

Patients with moderate to severe inflammatory acne vulgaris generally require systemic therapy for adequate control of their disease. Other indications for systemic therapy might include disease that has been unresponsive to topical treatment and cases with predominant involvement of the trunk, given the difficulty of treating wide body surface areas topically. Systemic agents to be discussed include antibiotics, antiandrogenic agents, and oral contraceptives. Intralesional injection of corticosteroids, which may be useful to suppress acute inflammation in larger inflammatory lesions, and isotretinoin (Accutane), the treatment of choice for severe nodulocystic or recalcitrant acne, are beyond the scope of this review.

Oral antibiotics. Table 5 lists the most commonly used oral antibiotics for acne, along with their drug interactions and adverse effects. These agents are useful in decreasing P acnes, free fatty acids in surface lipids, and inflammation (via their inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis).4,18 Improvement may not be noticeable until up to six to eight weeks after the start of therapy. It is usually necessary to continue the drugs for several months, with gradual tapering as tolerated once disease activity has stabilized or is beginning to resolve. Maintain patients on the lowest effective dose if long-term therapy is required.

TABLE 5

Commonly used oral antibiotics for acne

Use only in patients >8 yrs

Dairy products and other foods, antacids may decrease absorption

AR: photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, GI upset, teratogenic

PDI: penicillins, anticoagulants, OCPs

The resistance of P acnes to many antibiotics used to treat acne, including tetracycline, doxycycline, erythromycin, and clindamycin, has been documented.2426 This fact highlights the importance of avoiding indiscriminate prescribing of oral therapy, of continuing treatment for as short a time as necessary, and of avoiding therapy with multiple antibiotic classes either orally or topically. P acnes appears to be resistant to minocycline less often than to other antibiotics, even in patients who have demonstrated resistance to tetracycline or doxycycline.26

Both patients and parents frequently ask about the safety of long-term oral antibiotic therapy. In general, side effects are uncommon, and most of the agents, especially the tetracyclines, are well tolerated and well accepted by patients. Clinicians should clearly educate patients and parents about potential side effects and instruct patients to call if they experience any untoward symptoms. Routine laboratory testing is generally unnecessary, however. Always consider potential drug interactions and discuss them when indicated.

The tetracyclines are the treatment of choice if systemic antibiotic therapy is required. These drugs have a long track record of safety and efficacy in acne patients, although a variety of adverse reactions are possible. All of the tetracycline-class antibiotics may cause permanent yellow-gray-brown staining of teeth and enamel hypoplasia in patients 8 years old or younger and should not be used in this age group. The risk of photosensitivity is greatest with tetracycline and doxycycline and less of an issue with minocycline.

Dairy products or antacids taken concomitantly with any agent in this class may diminish drug absorption, but the absorption of only tetracycline is inhibited by all types of food. Patients should, therefore, take this medication one hour before or two hours after meals, which may translate into decreased compliance among active teenagers.

Potentially serious, albeit rare, drug reactions to minocycline have been reported with increasing frequency in the literature. They include pneumonitis, hepatotoxicity, drug-induced lupus (DIL), serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR), and a severe hypersensitivity syndrome reaction (HSR) characterized by fever, rash, and internal organ involvement.27 SSLR and HSR tend to occur within two months of commencing therapy, while DIL may be delayed in onset for two to six years.28 A study and literature review that examined the comparative safety of tetracycline, minocycline, and doxycycline found that minocycline was most commonly associated with these adverse reactions.28 Tetracycline and doxycycline caused HSR and SSLR rarely in comparison to minocycline, whereas all of the cases of DIL were associated with minocycline therapy.

Minocycline is the most widely prescribed systemic antibiotic for the treatment of acne vulgaris in the United States and Canada.29 If one considers the number of prescriptions in relation to the incidence of adverse reactions, the risk of a serious adverse reaction is exceedingly low. It should, however, be discussed with all patients considering therapy with a tetracycline antibiotic, especially minocycline. In addition, any patient with a history of one of these adverse events should probably be warned to avoid the tetracycline class of antibiotics in the future.

Erythromycin is another useful drug for acne vulgaris. The chief complaint of most patients taking this medication is gastrointestinal upset, which can be severe even with enteric-coated preparations. Reports of P acnes resistance to erythromycin also exist, as noted above. This agent may be helpful, however, for patients who cannot tolerate the tetracyclines or for whom photosensitivity is a problem.

Antiandrogenic agents. The primary goal of hormonal therapies for acne is to achieve an antiandrogen effect, with a resulting decrease in androgen-mediated changes such as sebum production. Treatment may also alleviate other undesirable signs of hyperandrogenism experienced by some patients, including hirsutism and menstrual irregularities.18 Antiandrogenic agents are often prescribed in consultation with a gynecologist or endocrinologist. Clinical features that may suggest a significant hormonal influence (and therefore a beneficial effect of this class of medications on acne) include later onset premenstrual flares in disease, predominance of lesions on the lower face (especially the jawline) and chin, excessive sebum production, hirsutism, and male-pattern alopecia.30

Antiandrogenic agents include spironolactone, flutamide, cyproterone acetate, gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists, and 5-

-reductase inhibitors. Most of these agents are best reserved for female patients. The antiandrogen employed most commonly for the treatment of acne vulgaris is spironolactone. This drug, which is used as a diuretic in the treatment of hypertension, is a competitive inhibitor of androgen receptors on target cells.30 It is quite effective at a dose of 50 to 200 mg/day, and may be used in conjunction with other acne therapies. Side effects include menstrual irregularities, breast enlargement and tenderness, and fatigue. Hyperkalemia may also occur.

Oral contraceptives

Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) may be very effective in treating acne vulgaris. Their potential mechanisms of action include suppression of androgen production and gonadotropin levels, decrease of free testosterone via increased serum levels of sex hormone-binding globulin, and inhibition of 5-

-reductase and androgen receptor binding.18,31 OCPs with a low-androgen progestin component appear to be most effective. One such product is triphasic norgestimate (0.18, 0.215, 0.25 mg) plus ethinyl estradiol (35 mg) (Ortho Tri-Cyclen). According to the prescribing insert, it is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for "the treatment of moderate acne vulgaris in females, >15 years of age, who have no known contraindications to oral contraceptive therapy, desire contraception, have achieved menarche and are unresponsive to topical anti-acne medications." In a study of 257 female patients with moderate acne, 93.7% treated with this preparation showed improvement, vs. 65.4% of those receiving placebo.32 Multiple other OCPs containing low-androgenicity progestins, such as norethindrone, desogestrel, and levonorgestrel, may likewise be useful in acne therapy.30 It may take three to six months for improvement to be noted, with slight worsening of the acne early in the course.18 I prescribe OCPs only in consultation with a gynecologist or endocrinologist.

Combination therapy

Because acne vulgaris is a multifactorial disorder and there are often multiple lesional types in the same patient, combination therapy using more than one of the above regimens is often necessary and tends to be more effective than monotherapy. An example of combination therapy is the use of a topical antibiotic in the morning and a topical retinoid in the evening for combined mild inflammatory and comedonal disease. Figures 1, 2, and 3 are "therapeutic vignettes" that present some options for combination therapy in patients with mild comedonal acne (Figure 1), mild inflammatory and comedonal acne (Figure 2), and moderate inflammatory and comedonal acne (Figure 3). These vignettes obviously serve only as examples; there are numerous other possible therapeutic combinations using the many available acne medications.

More art than science

Acne vulgaris is a common disorder with the potential for both medical and psychological complications. Treatment is best accomplished by thorough patient education and support combined with therapy directed at specific pathogenic factors.

Acne treatment is more art than science, and multiple factors play a role in therapeutic success, including patient motivation, compliance, and individual response patterns. Combination drug therapy with topical and systemic agents is often more successful than monotherapy. Treatments continue to be refined and should offer patients significant hope for improvement in their condition.

REFERENCES

1. Weiss JS: Current options for the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Pediatr Dermatol 1997;4(6):480

2. Pearl A, Arroll B, Lello J, et al: The impact of acne: A study of adolescents' attitudes, perception and knowledge. N Z Med J 1998;111(1070):269

3. Gupta MA, Gupta AK: Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 1998;139(5):846

4. Berson DS, Shalita AR: The treatment of acne: The role of combination therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32:S31

5. Leyden JL, McGinley KJ, Vowels B: Propionibacterium acnes colonization in acne and nonacne. Dermatology 1998;196(1):55

6. Leyden JL: Therapy for acne vulgaris. N Engl J Med 1997;336(16):1156

7. Nacht S, Gans EH, McGinley KJ, et al: Comparative activity of benzoyl peroxide and hexachlorophene. In vivo studies against propionibacterium acnes in humans. Arch Dermatol 1983;119(7):577

8. Haustein UF, Tegetmeyer L, Ziegler V: Allergic and irritant potential of benzoyl peroxide. Contact Dermatitis 1985;13(4):252

9. Gollnick H, Schramm M: Topical therapy in acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1998;11(Sl):S8

10. Leyden JL, Shalita AR: Rational therapy for acne vulgaris: An update on topical treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 15:907

11. Shalita A, Weiss JS, Chalker DK, et al: A comparison of the efficacy and safety of adapalene gel 0.1% and tretinoin gel 0.025% in the treatment of acne vulgaris: A multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:482

12. Lipson AH, Collins F, Webster WS: Multiple congenital defects associated with maternal use of topical tretinoin. Lancet 1993;341(8856):1352

13. Van Hoogdalem EJ: Transdermal absorption of topical anti-acne agents in man: Review of clinical pharmacokinetic data. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1998; 11(S1):S13

14. Lau H: Embryotoxicity and teratogenicity of topical retinoic acid. Skin Pharmacol 1993;6(Sl):35

15. Johnson EM: A risk assessment of topical tretinoin as a potential human developmental toxin based on animal and comparative human data. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36(3 Pt 2):S86

16. Parry MF, Rha CK: Pseudomembranous colitis caused by topical clindamycin phosphate. Arch Dermatol 1986;122(5):583

17. Milstone EB, McDonald AJ, Scholhamer CF: Pseudomembranous colitis, after topical application of clindamycin. Arch Dermatol 1981;117(3):154

18. Rothman KF: Acne update. Dermatol Ther 1997; 2:98

19. Feucht CL, Allen BS, Chalker DK, et al: Topical erythromycin with zinc in acne. A double-blind controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1980;3(5):483

20. Strauss JS, Stranieri AM: Acne treatment with topical erythromycin and zinc: Effect of Propionibacterium acnes and free fatty acid composition. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;11(1):86

21. Chalker DK, Shalita A, Smith JG, et al: A double-blind study of the effectiveness of a 3% erythromycin and 5% benzoyl peroxide combination in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 1983;9(6):933

22. Lin AN, Reimer RJ, Carter DM: Sulfur revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988;18(3):553

23. Graupe K, Cunliffe WJ, Gollnick HP, et al: Efficacy and safety of topical azelaic acid (20% cream): An overview of results from European clinical trials and experimental reports. Cutis 1996;57(l S):20

24. Eady EA, Jones C, Tipper J, et al: Antibiotic resistant propionibacteria in acne: Need for policies to modify antibiotic usage. BMJ 1993;306:555

25. Eady EA, Cove JH, Holland KT, et al: Erythromycin resistant propionibacteria in antibiotic treated acne patients: Association with therapeutic failure. Br J Dermatol 1989; 121(1):51

26. Eady EA, Jones CE, Gardner KJ, et al: Tetracycline-resistant propionibacteria from acne patients are cross-resistant to doxycycline, but sensitive to minocycline. Br J Dermatol 1993;128:556

27. Knowles SR, Shapiro L, Shear NH: Serious adverse reactions induced by minocycline. Report of 13 patients and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 1996;132:934

28. Shapiro LE, Knowles SR, Shear NH: Comparative safety of tetracycline, minocycline, and doxycycline. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:1224

29. Eichenfield AH: Minocycline and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Pediatr 1999;11:447

30. Shaw JC: Antiandrogen and hormonal treatment of acne. Dermatol Clin 1996;14(4):803

31. Burkman RT: The role of oral contraceptives in the treatment of hyperandrogenic disorders. Am J Med 1995;98(lA):130S

32. Lucky AW, Henderson TA, Olson WH, et al: Effectiveness of norgestimate and ethinyl estradiol in treating moderate acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37(5 Pt 1):746

DR. MANCINI is Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and Dermatology, Northwestern University Medical School, Children's Memorial Hospital, Chicago.

GUIDE FOR PATIENTS

The ABCs of acne

More than 90% of people have acne at some point in their lives. Many different factors play a role in the development of acne, which usually begins soon after puberty. At that time, increased hormones stimulate the production of sebuma substance produced by oil glands in the skin. If a hair folliclethe site of acnegets plugged with dead skin cells, sebum and bacteria may accumulate in this "plug." The result may be the dreaded zit, or, put more formally, a pimple.

Stress and emotional tension can sometimes trigger an outbreak of acne. Foods do not cause acne, although it helps to eat sensibly and in moderation.

Types of acne lesions

A blackhead forms when the pressure of sebum and dead cells forces the plug to the surface of the skin. The color of the blackhead is caused by skin pigment and dead skin cells. Blackheads are not caused by dirt, and dirt does not cause acne. Blackheads cannot be washed or scrubbed away.

A whitehead occurs when the plug remains below the surface of the skin.

When pressure from sebum and dead cells becomes too great, the trapped material may seep through the walls of the follicle and cause redness and discomfort. The result may be a pimple (papule) or pus bump (pustule). A cyst is a particularly deep and uncomfortable swelling.

Papules, pustules, and cysts may cause scarring. Although the scarring is permanent, a dermatologist may be able to perform certain procedures to improve the appearance of the skin.

What can be done

A number of treatments are available, depending on the severity and type of acne. Oral antibiotics, which decrease inflammation and reduce the amount of bacteria inside the body, are most effective for acne characterized by many papules, pustules, and cysts.

Topical antibioticsthose applied directly to the skin as a lotion, gel, or creamdestroy bacteria on the skin, and may be used alone or in combination with other drugs.

Benzoyl peroxide is a peeling agent that dries the skin and helps prevent the growth of bacteria. Topical Vitamin A (Retin-A), another peeling agent, loosens the plugs of skin cells. It is most helpful for blackheads and whiteheads.

Isotretinoin (Accutane) is an oral medication that should be used for only severe forms of acne, since it is associated with many side effects.

Some acne "don'ts"

- Avoid cosmetics and skin creams, if possible. If you do wear cosmetics, use those that are water-based or oil-free. Use only skin creams that do not cause acne, such as non-comedogenic facial moisturizers.

- Washing and scrubbing with harsh soaps and brushes may make acne worse, not better. It can also dry and irritate the skin. It is usually best to clean your skin gently and to use mild soaps or acne bars.

- Sunlight and tanning beds may improve the way your skin looks by causing it to peel. But the improvement is only temporary. What's more, sunlight is an important cause of aging and wrinkling of the skin, and it may lead to skin cancer.

ACCREDITATION

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essentials and Standards of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Jefferson Medical College and Medical Economics, Inc.

Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, as a member of the Consortium for Academic Continuing Medical Education, is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to sponsor continuing medical education for physicians. All faculty/authors participating in continuing medical education activities sponsored by Jefferson Medical College are expected to disclose to the activity audience any real or apparent conflict(s) of interest related to the content of their article(s). Full disclosure of these relationships, if any, appears with the author affiliations on page 1 of the article.

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION CREDIT

This CME activity is designed for practicing pediatricians and other health-care professionals as a review of the latest information in the field. Its goal is to increase participants' ability to prevent, diagnose, and treat important pediatric problems.

Jefferson Medical College designates this continuing medical educational activity for a maximum of one hour of Category 1 credit towards the Physician's Recognition Award (PRA) of the American Medical Association. Each physician should claim only those hours of credit that he/she actually spent in the educational activity.

This credit is available for the period of December 15, 2000, to December 15, 2001. Forms received after December 15, 2001, cannot be processed.

Although forms will be processed when received, certificates for CME credits will be issued every four months, in March, July, and November. Interim requests for certificates can be made by contacting the Jefferson Office of Continuing Medical Education at 215-955-6992.

HOW TO APPLY FOR CME CREDIT

1. Each CME article is prefaced by learning objectives for participants to use to determine if the article relates to their individual learning needs.

2. Read the article carefully, paying particular attention to the tables and other illustrative materials.

3. Complete the CME Registration and Evaluation Form below. Type or print your full name and address in the space provided, and provide an evaluation of the activity as requested. In order for the form to be processed, all information must be complete and legible.

4. Send the completed form, with $20 payment if required (see Payment, below), to:

Office of Continuing Medical Education/JMC

Jefferson Alumni Hall

1020 Locust Street, Suite M32

Philadelphia, PA 19107-6799

5. Be sure to mail the Registration and Evaluation Form on or before December 15, 2001. After that date, this article will no longer be designated for credit and forms cannot be processed.

FACULTY DISCLOSURES

Jefferson Medical College, in accordance with accreditation requirements, asks the authors of CME articles to disclose any affiliations or financial interests they may have in any organization that may have an interest in any part of their article. The following information was received from the author of "Acne vulgaris: A treatment update."

Anthony J. Mancini, MD, has nothing to disclose.

Anthony Mancini. Acne vulgaris: A treatment update. Contemporary Pediatrics 2000;12:122.

Recognize & Refer: Hemangiomas in pediatrics

July 17th 2019Contemporary Pediatrics sits down exclusively with Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD, a professor dermatology and pediatrics, to discuss the one key condition for which she believes community pediatricians should be especially aware-hemangiomas.

Itchy skin associated with sleep problems in infants

September 27th 2024A recent study presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2024 National Conference & Exhibition, sheds light on the connection between skin conditions and sleep disturbances in infants and toddlers, highlighting itchy skin as a significant factor, even in the absence of atopic