Environment, geography, and genes: More nature, less nurture when it comes to ASD?

“It is well known that autism has a strong genetic component; that’s indisputable, but my interpretation [of this latest study] is that environmental insult also has a very strong effect.” The remark comes from Andrey Rzhetsky, PhD, Pritzker Scholar and professor of Genetic Medicine and Human Genetics at the University of Chicago, Illinois.

“It is well known that autism has a strong genetic component; that’s indisputable, but my interpretation [of this latest study] is that environmental insult also has a very strong effect.”

The remark comes from Andrey Rzhetsky, PhD, Pritzker Scholar and professor of Genetic Medicine and Human Genetics at the University of Chicago, Illinois. He’s talking about his recent study examining how various environmental factors affect the incidence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and intellectual disability (ID).1

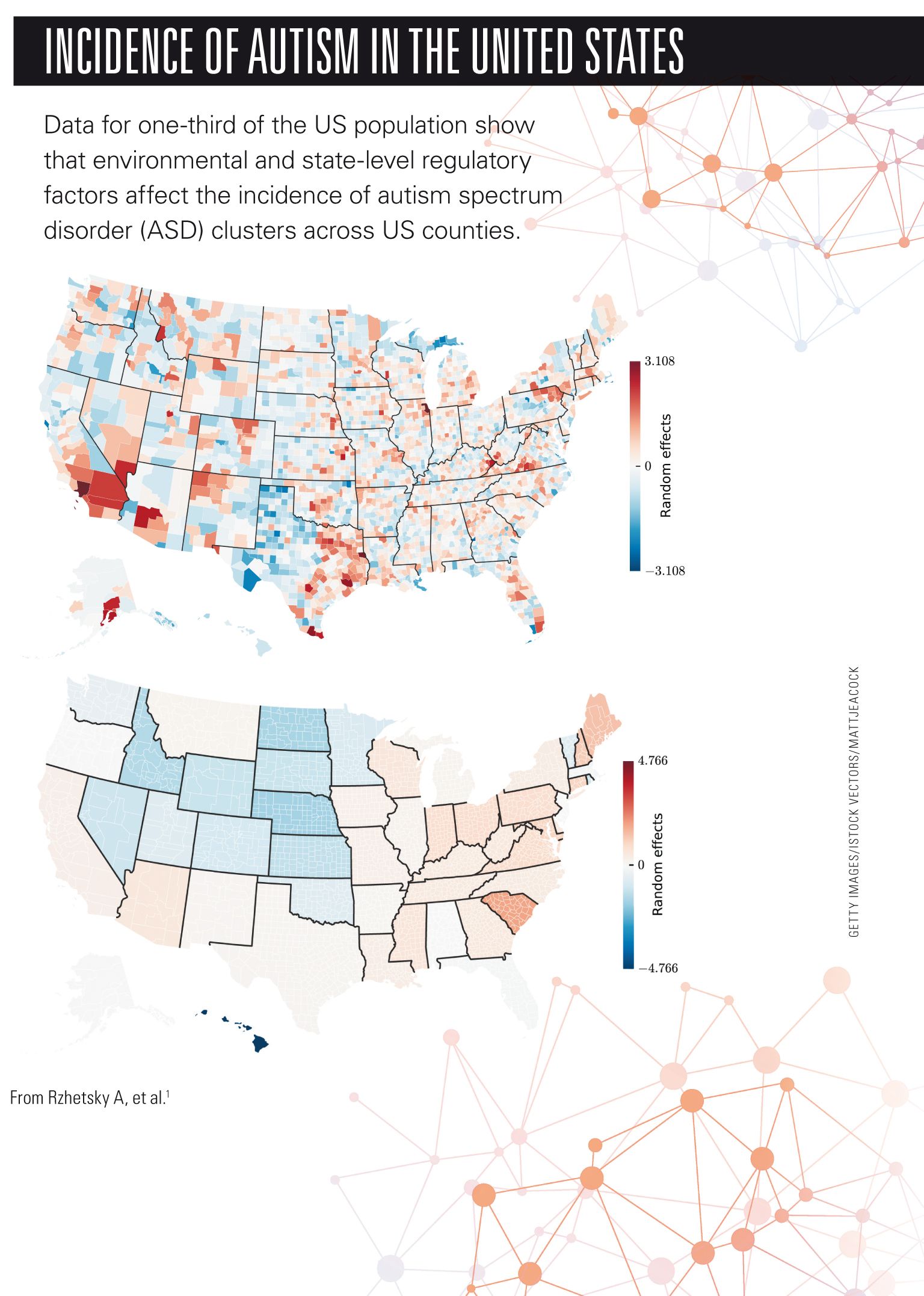

To compare environmental, phenotypic, socioeconomic, and state-policy factors in a unified framework, Rzhetsky and his colleagues analyzed the spatial incidence patterns of ASD and ID using an insurance claims dataset covering nearly one-third of the US population. The analysis found that ASD and ID display strong variation in incidence across the United States, just as diseases such as cancer do; that US counties with high rates of ASD also have high rates of ID; and that the incidences of both are impacted by environmental and economic factors.

More specifically, they found that ASD incidence rates are strongly linked to rates of congenital malformations of the reproductive system in males. In fact, for every 1% increase in the incidence of those malformations above the US mean incidence, the incidence of ASD increases by 283%.

Why look at male reproductive congenital malformations? That’s because the defects serve as a surrogate measure for environmental burden, explains Rzhetsky. They indicate environmental exposure to unmeasured developmental risk factors, such as toxins, pesticides, environmental lead, certain medications, and/or plasticizers, just to name a few. Congenital birth defects also have been linked to certain parental occupations, including that of janitor, maid, and landscaper.

Similarly, the researchers found that every 1% increase in the incidence of nonreproductive congenital malformations predicted an increase in the ASD rate by 31.8%, and every 1% increase in the incidence of viral infections in males predicted an increase in the ASD rate by 19%. They found similar relationships with IDs, but most were not quite as dramatic.

The investigators found the second-strongest environmental influence on apparent ASD incidence to be state-level regulations involving ASD. Not surprisingly, the stricter and narrower the definition of autism used by the state for consideration of a child’s participation in a special education program, the lower the ASD and ID incidence rates.

Rzhetsky says his team also confirmed that girls are 4 to 5 times less likely to receive an ASD diagnosis than boys. Several other incidental findings included that as income rises, so does the likelihood of a diagnosis of ASD, and being a Pacific Islander is protective.

He explains that part of what makes this study unique is that his researchers were able to use a huge insurance database covering nearly one-third of the US population-well over 100 million unique patients-and covering every US county. They also used information from the US Census Bureau to help account for confounders.

Still, Rzhetsky is cautious not to overinterpret his findings. “We clearly understand that correlation is not causation; we have shown a significant correlation, but we can interpret the results in many ways. The most likely interpretation, in our view,” he says, “is that there is environmental influence.”

Martha R. Herbert, MD, PhD, pediatric neurologist and neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and author of the book The Autism Revolution. Whole-body Strategies for Making Life All It Can Be,2 says that we’ve known about clusters as they relate to autism for some time. She comments that what’s “remarkable about this study are the sheer numbers” involved.

She says using congenital malformations of the reproductive system in males as an indicator of environmental insult “makes sense.” Conditions such as hypospadias are “unambiguous.” In other words, “you either have it or you don’t.” These conditions are associated with environmental toxicity.

“I found it particularly interesting,” Herbert continues, “that the nonreproductive male congenital malformations correlated more with intellectual disability, while the reproductive ones correlated more with autism.” She wonders if this might somehow explain why so many more boys are affected by autism than girls. She says it’s another piece in the puzzle pointing to involvement of hormones, hormone disruption, and/or endocrine disruption impacting neurodevelopment.

“We can’t assume that autism is genetically predetermined or that there’s nothing to do about it,” she concludes. “People need to realize that there’s more to the story than we said 5 or 10 years ago. They should be open to the possibility that there might be things we may be able to do to reduce the risk during pregnancy and infancy.”

Rzhetsky philosophically concludes with regard to the cause of autism, “If it’s purely genetic, it may appear to be hopeless, but if there is an environmental component, then there’s something we can change and, hopefully, treat. Of course, it’s both.”

REFERENCES

1. Rzhetsky A, Bagley SC, Wang K, et al. Environmental and state-level regulatory factors affect the incidence of autism and intellectual disability. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014; 10(3):e1003518. Available at: www.ploscompbiol.org/article/info:doi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pcbi.1003518. Accessed March 27, 2014.

2. Herbert M. The Autism Revolution. Whole-body Strategies for Making Life All It Can Be. New York: Ballantine Books; 2012. Available at: www.autismrevolution.org/. Accessed March 27, 2014.

Ms Hack is a medical writer and editor in New Jersey. She has 25 years’ experience in the field and is a long-time contributor to both Contemporary Pediatrics and sister publication Contemporary OB/GYN. She has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.