Photo Essay: Images of Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one the most important infectious diseases in the world. More than 8 million people are infected every year. The vast majority of infections--95%--occur in developing countries, where the disease accounts for 25% of avoidable adult deaths.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one the most important infectious diseases in the world. More than 8 million people are infected every year. The vast majority of infections--95%--occur in developing countries, where the disease accounts for 25% of avoidable adult deaths. The incidence of this disease is increasing in sub-Saharan Africa and the countries of the former Soviet Union. Poverty, neglect of TB control programs, changes in population demographics (migration, aging), and the impact of HIV infection are all responsible.1

The diagnosis of TB is particularly difficult to make in children. Clinical findings are usually nonspecific, and mycobacteria are difficult to obtain. (In children, 95% of pulmonary TB cases are smear-negative for acid-fast bacilli.) Moreover, the risk of disease progression and dissemination is much higher in children than in adults. There is a 5% to 10% lifetime risk that TB will develop in an infected adult. In children, the risk of active disease after infection is 43% in the first year of life; this risk decreases to 24% in children 1 to 5 years old, and to 15% in those between ages 11 and 15 years. Co-infection with HIV or other viruses (particularly measles), malnutrition, and other chronic illnesses dramatically increase the risk of progression from latent infection to active disease.2

Primary and Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Most children become infected through aerosol droplets from adult source cases. Mycobacterial multiplication occurs in alveolar macrophages surrounded by local inflammation (primary focus). From here, bacteria spread locally to regional lymph nodes (primary complex) or by early hematogenous dissemination to other organs. Cellular immunity develops within 2 to 12 weeks; this leads to the typical hypersensitivity responses of reactive tuberculin skin testing (Figure 1), phlyctenular conjunctivitis (Figure 2), erythema nodosum (Figure 3), and serous effusions in the peritoneum, pleura, or joints (Ponçet's disease).

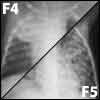

Progression from a primary complex to primary TB is common in children. Lymphatic spread to hilar, peribronchial, or subcarinal mediastinal nodes causes endobronchial disease or local obstructive hyperinflation and/or collapse-consolidation (Figures 4 and 5). Possible outcomes include resolution of the local inflammation, residual calcification of segmental lesions, scarring and lobar contraction typically associated with bronchiectasis of obstructed bronchioles, or progressive inflammation with central caseous necrosis. Subpleural primary foci or lymph nodes frequently discharge bacilli into the pleural space; for this reason, persons with primary pulmonary TB commonly have an exudative pleural effusion (Figure 6).

Progressive pulmonary TB develops if the primary complex does not heal or calcify. The complex enlarges and forms a large caseous necrotic center, which may empty into a bronchus, leaving behind a cavity (Figure 7). Subcarinal nodes may drain into the pericardial sack causing tuberculous pericarditis. Serofibrinous exudates eventually lead to fibrosis of the pericardium and constrictive pericarditis with superior and inferior vena cava congestion, hepatomegaly, and ascites (Figure 8).3

Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis

Lymphohematogenous spread of TB in children occurs early in the incubation period. It may remain occult and manifest months later as extrapulmonary TB. It may also manifest clinically as overwhelming miliary TB--typically in infants within the first few weeks after infection. Miliary TB may also be the consequence of a tuberculous focus (typically a lymph node) draining into a blood vessel. In patients with miliary TB, numerous lesions can be found in the lungs, liver, spleen, skin, bone marrow, myocardium, and brain (Figure 9).4

Tuberculous meningitis is the result of lymphohematogenous spread or miliary dissemination of the disease: it occurs in about 2% of infected children. The base of the brain is most commonly affected by thick exudates that tend to obstruct cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow. Basilar vascular enhancement, infarcts as a consequence of vasculitis, and hydrocephalus are the radiologic hallmarks of the disease (Figure 10). Focal nerve deficits typically involve the third and sixth cranial nerves and the optic chiasm.

Clinically, stage 1 disease presents with insidious onset of meningitis without focal neurologic deficits. Stage 2 disease (with neurologic deficits) carries an increased risk of long-term morbidity. Stage 3 disease with neurologic deficits and altered mental status bears grave long-term morbidity and mortality.

CSF pleocytosis, initially polymorphonuclear, becomes lymphocyte-predominant. The protein content of the CSF is elevated, with low or low-normal glucose levels. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion with low serum sodium levels is common. A tuberculin skin test is reactive in only half of those with tuberculous meningitis, which suggests either an overwhelming infection or a compromised immune response.5

Tuberculomas, on the other hand, are typically associated with a strong tuberculin skin test response. They present clinically as local mass lesions with focal neurologic deficits representing the site of disease (Figure 11). They may also evolve during the treatment of miliary TB or tuberculous meningitis as the immune system recovers.

Tuberculous osteomyelitis develops in 1% to 5% of infected children. It typically results from an endarteritis in the metaphyses of growing weight-bearing bones after hematogenous spread ofmycobacteria. Most commonly affected are the vertebral bodies of the thoracic spine (40%), where contiguous spread from para-aortic lymph nodes adds to the hematogenous source of infection. The disease typically affects the anteroinferior part of a vertebral body and spreads to the anterosuperior aspect of the adjacent vertebra along the anterior spinal ligament. This leads to a wedge-shaped deformity, or gibbus (Pott disease). Paravertebral cold abscesses and neurologic deficits from spinal cord compression can be expected in 10% to 30% of patients. Evolving nerve or cord compression requires careful surgical stabilization of the affected spine(Figures 12 and 13).6

Regional lymph nodes are virtually always affected by primary TB, and their location may indicate the port of entry of the infection. They may also be a manifestation of lymphohematogenous dissemination presenting as generalized lymph node enlargement associated with fever, malaise, weight loss, and a reactive tuberculin skin test. Localized supraclavicular adenopathy occurs as a consequence of contiguous spread from an underlying pulmonary focus.

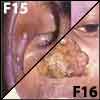

Cutaneous drainage and fistula formation are common (scrofuloderma) (Figure 14). Lymphohematogenous spread to the skin leads to papulonecrotic tuberculids (multiple small miliary tubercles) (Figure 15) or TB verrucosa cutis (large, confluent tuberculids). Lupus vulgaris is a chronic indolent form of tuberculid typically found on the face (Figure 16).2

Diagnosis

According to the World Health Organization, the diagnosis of "confirmed tuberculosis" requires the identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by microscopy or culture of tissue samples or secretions, with or without the help of polymerase chain reaction amplification.7 This may be possible in advanced pulmonary or extrapulmonary disease, but is virtually impossible in most children with limited infection.

The WHO guidelines suggest a diagnosis of "suspected tuberculosis" in:

•An ill child with a confirmed adult source case.

•A child who does not regain his or her previous state of health after a bout of measles or whooping cough.

•A child who does not recover from a respiratory infection despite antibacterial chemotherapy.

•A child with painless superficial lymphadenopathy.

A diagnosis of "probable tuberculosis" is considered:

•In a child with suspected disease who also has a reactive tuberculin skin test that exceeds 10 mm.

•In a child with a suggestive chest radiograph.

•When the results of histologic evaluation of a biopsy specimen are suggestive.

•When the response to antituberculous therapy is favorable.7,8

Tuberculin skin test results have a good positive predictive value in high-prevalence communities but a very low predictive value in low-risk environments. The American Academy of Pediatrics therefore recommends screening skin tests only for children with identified source case contacts, children who have household members with reactive skin tests, and children born in or traveling for prolonged periods to countries in which disease prevalence is high. Children with clinical or radiologic features that suggest TB should also be tested, along with HIV- infected children, homeless or incarcerated adolescents, and children with ongoing exposure to high-risk populations (Table 1).8-10

Treatment

In children with TB, the mainstay of therapy is isoniazid (INH). The drug is easily absorbed orally, diffuses readily to all tissues, and has a relatively benign toxicity profile. Side effects include peripheral neuritis (from pyridoxine inhibition) and hepatitis.

Rifampin is as bactericidal to M tuberculosis as INH is. The medication is also readily absorbed and distributed to all tissues. Hepatotoxicity may be exacerbated by concurrent INH therapy. Patients need to be told that rifampin renders oral contraceptives ineffective and that bodily secretions turn orange (affecting contact lenses) during treatment with this drug.

Pyrazinamide readily reaches therapeutic levels in the CSF and macrophages; maximal effect occurs during the first 2 months of therapy. Hepatotoxicity may be encountered at higher doses, together with cutaneous hypersensitivity, arthralgia, and gout.

Ethambutol is a bacteriostatic drug more commonly used in adults. Potentially irreversible optic neuritis limits the use of this drug to multidrug-resistant cases of TB in children. Ethionamide is better tolerated by children. It diffuses readily into the CSF and can be given as additional drug in tuberculous meningitis or as part of a combination regimen in drug-resistant cases.

Streptomycin and other aminoglycoside antibiotics are also effective as part of a combination regimen in the initial phases of treatment plans for drug-resistant TB. The requirement for daily intramuscular injections for 4 to 8 weeks limits their use in children.8,9

Recommended treatment plans for children with latent or suspected/ confirmed TB are outlined in Table 2.

Wrap-Up

TB remains one of the world's most prevalent diseases and is a cause of significant morbidity and mortality. Bacteriologic diagnosis is difficult in children, who are at particularly high risk for disease progression. Those in high-risk populations need to be identified and tested with tuberculin skin tests. Therapy is prolonged and requires a regimen of 3 or more concurrently administered drugs.

Adherence to TB control programs, the alleviation of poverty and malnutrition, and a reduction in the prevalence of HIV will be necessary to have a meaningful impact on the disease.

References:

REFERENCES:

1.

Maher D, Raviglione M. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis.

Clin Chest Med.

2005;26:167-182, v.

2.

Feja K, Saiman L. Tuberculosis in children.

Clin Chest Med.

2005;26:295-312, vii.

3.

Cremin BJ, Jamieson DH.

Childhood Tuberculosis: Modern Imaging and Clinical Concepts.

Berlin: Springer; 1995.

4.

Sharma SK, Mohan A, Sharma A, Mitra DK. Miliary tuberculosis: new insights into an old dis-ease.

Lancet Infect Dis.

2005;5:415-430.

5.

Thwaites GE, Tran TH. Tuberculous meningitis: many questions, too few answers.

Lancet Neurol.

2005;4:160-170.

6.

Gardam M, Lim S. Mycobacterial osteomyelitis and arthritis.

Infect Dis Clin North Am.

2005;19: 819-830.

7.

World Health Organization.

WHO Tuberculosis Programme Framework for Effective Tuberculosis Control.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994.

8.

Shingadia D, Novelli V. Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in children [published correction appears in

Lancet Infect Dis.

2004;4:251].

Lancet Infect Dis.

2003;3:624-632.

9.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Tuberculosis. In: Pickering LK, ed.

Red Book: 2003 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases.

26th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003: 642-660.

10.

Reznik M, Ozuah P. Tuberculin skin testing in children.

Emerg Infect Dis.

2006;12:725-728.

The Role of the Healthcare Provider Community in Increasing Public Awareness of RSV in All Infants

April 2nd 2022Scott Kober sits down with Dr. Joseph Domachowske, Professor of Pediatrics, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and Director of the Global Maternal-Child and Pediatric Health Program at the SUNY Upstate Medical University.