Reeducating peds to counsel for contraception

The results of 2 recent studies indicate that although teenaged pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are significantly lower than in previous years, there is still much room for improvement.

The results of 2 recent studies indicate that although teenaged pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are significantly lower than in previous years, there is still much room for improvement. Clinicians can take a number of steps including adjusting their attitudes toward contraception and their understanding of up-to-date efficacy and safety issues with each method. A better implementation of educational interventions for both physicians and their patients would be useful as well.

More: Contraception guidelines for adolescents

“Teen pregnancy rates in the [United States] have fortunately been on the decline over the last years. However, they continue to be higher than those of other comparable, developed nations including Canada and European countries,” says Kate J. Swanson, MD, Department of Obstetrics, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois. “This clearly reflects an area where we as providers could improve. There is no quick fix for this significant and complicated health issue, and a better understanding of the different factors involved here could greatly help our patients,” she says.

Beliefs and prescribing patterns

Swanson and colleagues recently conducted a provider survey study to help elucidate pediatricians’ beliefs and prescribing patterns in their adolescent patients. In the study, general pediatricians and pediatric residents affiliated with the Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago were asked to complete a survey regarding adolescent contraception that included questions related to obtaining information about contraception, contraceptive counseling, knowledge of contraceptive methods, prescribing patterns of contraceptives, and concerns about individual contraceptive methods.

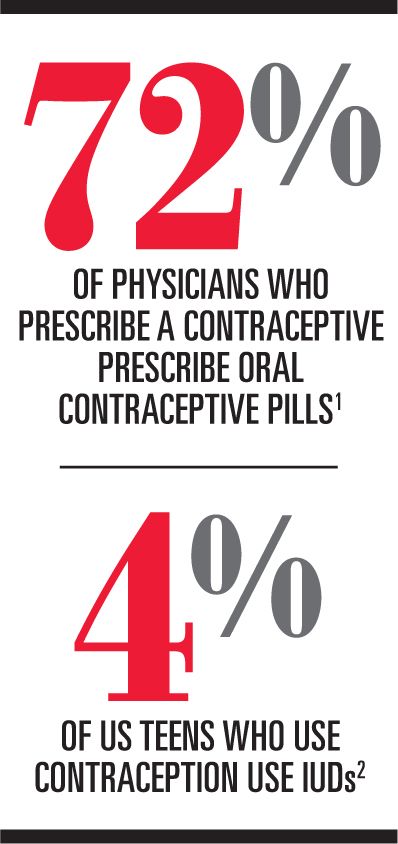

Of the 411 eligible physicians, 120 (29%) took part in the survey. The researchers found that 79% of participants had prescribed at least 1 contraceptive method, the most common being oral contraceptive pills (72%).1 Data also showed a number of differences in the clinicians’ prescribing patterns of contraceptives, and, interestingly, there were numerous misconceptions among the participants including a high rate of concern about the risk of infertility with intrauterine device (IUD) use, seen in 29% of physicians who prescribed at least 1 method of contraception.

Physicians’ attitudes toward contraception counseling with adolescents, Swanson says, appear to be one of the many barriers to increasing adolescents’ access to contraception. Interestingly, one of the biggest reasons for the clinicians who did not provide any contraception method to their patients was their own lack of familiarity with contraception.

“Clinicians who haven’t had an adequate focus in training on contraception may be unaware of certain options or have misconceptions about them, and, therefore, their patients may not necessarily be getting the most up-to-date or full contraception options,” says Swanson. “As a result, many adolescent patients may not see an obstetrician or gynecologist until they are pregnant or have an STI. We need to confront this issue head-on and believe that the implementation of educational interventions for both patients and clinicians is key,” she adds.

Practices and attitudes

Similar results regarding teenaged pregnancy, STIs, and the general practices and attitudes of general providers were echoed in another recent study performed by Susan E. Rubin, MD, MPH, assistant professor, Department of

Family and Social Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York. Here, Rubin and colleagues conducted a study exploring primary care providers’ (PCPs) clinical practice with their adolescent patients regarding contraception counseling and, in particular, their views on the use of IUDs and ideal candidates for this mode of contraception.

Read: Tackling declining HPV vaccine rates in teens

In the study, the researchers conducted telephone interviews with 28 urban family physicians, pediatricians, and obstetrician-gynecologists. Data showed that although most of the participating physicians have a patient-centered approach with general contraceptive counseling, when assessing and considering adolescents’ eligibility for an IUD, many PCPs take a more paternalistic approach. Although many respondents said they believe that the primary concern of adolescents may be pregnancy prevention, in some instances participating physicians do not offer IUDs because of their prioritization of adolescent condom use for STI prevention.2

According to Rubin, the complex challenges currently seen in teenaged pregnancy and STI prevention are likely associated with many different factors including healthcare systems issues in terms of access to contraception, confidential care for adolescents, co-pays, time per visit, and the attitudes PCPs have toward adolescent sexual behavior.

“As a family physician, I really feel that discussion of pregnancy and STI prevention is the bread and butter of primary care for teens, given our high teen pregnancy and STI rates,” says Rubin. “A lot of my research focuses on how to increase adolescents’ access to full-scope contraception within primary care and how to do this better without focusing on any one contraception method in particular.”

There appears to be a competing concern among practitioners between STI prevention and pregnancy prevention, Rubin says. Although condom use can help prevent both pregnancy and STIs, they are by far not the most effective contraceptive. Beyond abstinence and safe-sex approaches, there are a multitude of contraceptive methods currently available for patients. In terms of the reversible approaches, Rubin says that the most efficacious contraceptive options are IUDs and implantable contraception.

Most adolescents are eligible candidates for these methods because there are very few contraindications for their use. However, whether the methods align with an adolescent girl's needs and priorities in terms of what she is looking for in contraception remains another issue. Implantable contraception and IUDs are safe and effective for adolescent girls and nulliparous women, Rubin says, contrasting older concerns that their use might increase the risk of pelvic infection and potentially jeopardize the woman’s future fertility. According to Rubin, this data has been debunked.

“The only increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease with IUDs is within the first 21 days postinsertion, and that is thought to be due to an untreated STI at the time of insertion,” Rubin points out. “In fact, we can perform STI testing and IUD insertion on the same day, and contact the patient if she should test positive for STI. We do not have to remove the device in this scenario and treating STI with the IUD in place has now become the standard of care,” she explains.

According to Rubin, 4% of US adolescents who use contraception use IUDs. The reasons for low use are many, Rubin says, one of which is that clinicians are just starting to get over the legacy of the dangers associated with Dalkon Shield IUDs developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As a result, many clinicians have not been trained in IUD placement.

Condoms are not an ideal method for pregnancy prevention. The message promoting their use may be falling on deaf ears, particularly when one looks at the pregnancy and STI rates in the United States. According to Rubin, the message needs to be changed to a new and more emphatic message-perhaps condoms plus another mode of contraception. Although prescription contraception cannot impact the rate of STIs, it can assist in decreasing unintended pregnancy rates.

“Certainly, [human papillomavirus (HPV)] vaccines can help prevent against STIs as well, so getting an HPV vaccination is a good thing for different reasons. However, not allowing adolescents access to contraception because of concerns that they won’t use a condom is detrimental,” Rubin says.

What’s the answer?

Reframing a more effective message for STI and pregnancy prevention may be key to accepting contraception. Appropriate and up-to-date education of patients as well as clinicians’ regard for the safety of modern contraceptive methods is crucial and should be one of the cornerstone approaches. The high safety of modern contraceptives is reflected in the ongoing debate as to whether oral contraceptive pills, particularly progesterone-only pills, should be available over the counter. Abolishing the prescription mandate for prescription contraceptive pills could likely increase adolescents’ access to them, Rubin says, which could impact pregnancy rates.

“I think that practitioners are all talking about contraception at some point and want to include this in their patient consultations,” says Swanson. “However, I think that when they don’t have the most up-to-date or complete information, they can’t adequately do that, underscoring the importance of education and up-to-date safety and efficacy data on all contraceptive methods,” she adds.

More: Emergency contraception update

Some physicians also may have to come to terms with their own values and convictions regarding adolescent sexual behavior and prescribing contraception in this age group. Although likely a small minority, some clinicians may not want to prescribe contraception for their patients. According to Rubin, one of the challenges is for practitioners to have a healthier and more open attitude with their patients regarding adolescent sexual behavior. One reason why US pregnancy rates are so high may be because of the denial that teenagers are having sexual relations, a societal attitude that needs to be adjusted for the benefit and health of patients. Moreover, abstinence pledges do not appear to be working well.

“If ours is a society that supports this abstinence-only approach and [is] not educating our kids about how to prevent pregnancy other than abstinence, we are doing them a disservice both for pregnancy and STIs,” Rubin says.

Several years ago, after extensive research, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) put forth new eligibility criteria for contraception initiation and continuation, underscoring the high safety for all contraceptive methods. Rubin actively performs education interventions in primary care pediatric practices trying to increase pediatricians’ comfort with full-scope contraception counseling and provision as well as managing expected adverse effects. Because adolescents are not the bulk of most pediatric practices, Rubin says, pediatricians might not be comfortable with prescribing the many different contraceptive methods available.

“I’ve observed a disproportionate concern that contraceptives are not safe for many teens,” says Rubin. “My research has shown that not a lot of pediatricians are comfortable talking about the range of contraceptive options with their patients. Increasing a clinician’s comfort here is challenging and I think that educating them about the CDC medical eligibility criteria can be helpful, giving some specific patient information on what to expect and how to manage expected [adverse] effects,” she says.

Time is perhaps one of the most important factors in effective contraception counseling, Rubin points out. Clinicians should try to spend more time with their patients to find out what they really want and value in contraception and which mode of contraception could best suit their individual needs and situation.

“There are so many factors that need to change,” says Rubin. “How do we affect behavior change at all, and if we are talking about behavior change for clinicians, I have to change my attitudes and my belief that these methods of contraception are safe. I have to change the script in my head that I use when I’m talking about this.”

Rubin suggests, “A multipronged approach is needed to help decrease the risk of STIs and teen pregnancy, but we all need to be on the same page first.”

Dr Swanson and Dr Rubin have nothing relevant to disclose.

REFERENCES

1. Swanson KJ, Gossett DR, Fournier M. Pediatricians’ beliefs and prescribing patterns of adolescent contraception: a provider survey. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26(6):340-345.

2. Rubin SE, Campos G, Markens S. Primary care physicians' concerns may affect adolescents' access to intrauterine contraception. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(3):216-219.

Ten tips for parents to help their children avoid teen pregnany (English)

bit.ly/CP-10-tips-to-avoid-teen-pregnancy-English

Diez consejos para los padres: Para ayudar a sus hijos a evitar el embarazo en la adolescencia (Spanish)

bit.ly/CP-10-tips-to-avoid-teen--pregnancy-Spanish

Dr Petrou is a freelance medical writer based in Budapest, Hungary. He has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.

Having "the talk" with teen patients

June 17th 2022A visit with a pediatric clinician is an ideal time to ensure that a teenager knows the correct information, has the opportunity to make certain contraceptive choices, and instill the knowledge that the pediatric office is a safe place to come for help.

Meet the Board: Vivian P. Hernandez-Trujillo, MD, FAAP, FAAAAI, FACAAI

May 20th 2022Contemporary Pediatrics sat down with one of our newest editorial advisory board members: Vivian P. Hernandez-Trujillo, MD, FAAP, FAAAAI, FACAAI to discuss what led to her career in medicine and what she thinks the future holds for pediatrics.

Study finds reduced CIN3+ risk from early HPV vaccination

April 17th 2024A recent study found that human papillomavirus vaccination when aged under 20 years, coupled with active surveillance for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2, significantly lowers the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or cervical cancer.