- Vol 37 No 7

- Volume 37

- Issue 7

Could fever improve COVID-19 outcomes?

Most fevers are good, not bad. Here’s why pediatricians should respect fever.

Humans do not have any natural immunity to COVID-19. We do not have an effective antiviral medication for nonhospitalized patients. We do not have a vaccine and may not for at least a year. Perhaps we should optimize the human body’s natural response to infections. To us, that means helping fever do its job.

When the body is invaded by a new germ, it mounts a fever. The fever ramps up our immune system, which is necessary to fight infections.1 All warm-blooded animals get fevers when they have infections. Every aspect of our immune system works better at a higher temperature. Was that a design flaw? Why would our bodies waste energy on something that isn’t helpful?

Dogs, rabbits, mice, ferrets, lizards, fish, and other species have been studied for what happens if we inject them with germs and suppress their fever. They have a higher death rate.2-5 Humans should be no different. Yet you ask: Are there similar studies on humans?

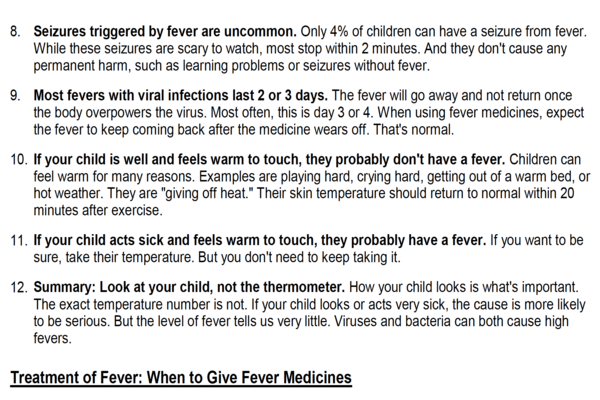

Research has shown that people with infections who are treated with fever-reducing medicines have symptoms that often are more severe and last longer than those who don’t take antifever medicines.6-10 These articles on rhinovirus, influenza, chickenpox, and other respiratory infections all showed improved outcomes if the associated fever was not treated. To date, there is no published research that shows treating fevers with antipyretics improves outcomes.

Treating fever from vaccines

What about fever from vaccines? Two studies looked at what happens if we give prophylactic antipyretics to young children before or immediately after vaccines.11,12 Both found that antipyretics cause a lower antibody response when measured one month later.

Obviously, our views apply to all viral infections, not just the dangerous one that currently holds center stage. We would suggest health care professionals stop interfering with the human body’s attempt to cure itself. Here’s how we might do that:

- Respect the known benefits of fevers.

- Understand that the human body has a thermostat in the hypothalamus that keeps the fever in the optimal range for fighting infections.

- Do not treat all fevers with antipyretics (acetaminophen or ibuprofen).

- Never treat with combination (dual) antipyretics. It’s one of the main causes of fever phobia, mainly propagated by physicians and nurses.

- Keep patients well hydrated so they can easily give off heat by sweating if they need to.

- Teach the public that most fevers are good, not bad. Teach that reducing fevers may make you feel better but delay your recovery.

- Teach the public that every time we give an antipyretic, we dampen the body’s natural immune response. That’s why the fever always returns when the medicine wears off.

In summary, there is evidence that fever improves outcomes for infections. Of note, there is no evidence to the contrary. Let’s be evidence based.

The human body wants to recover, to survive. Shouldn’t we support that?

References

- Evans SS, Repasky EA, Fisher DT. Fever and the thermal regulation of immunity: The immune system feels the heat. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015:15(6):345-349.

- Kluger MJ, Ringler DH, Anver MR. Fever and survival. Science. 1975:188(4184):166-168.

- Bernheim HA, Kluger MJ. Fever: effect of drug-induced antipyresis on survival. Science. 1976:193(4249):237-239.

- Kluger MJ. Fever revisited. Pediatrics. 1992:90(6):846-850.

- Rodbard D. The role of regional body temperature in the pathogenesis of disease. N Engl J Med. 1981:305(14):808-814.

- Stanley ED, Jackson GG, Panusarn C, Rubenis M, Dirda V. Increased virus shedding with aspirin treatment of rhinovirus infection. JAMA. 1975:231(12):1248-1251.

- Doran TF, De Angelis C, Baumgardner RA, Mellits ED. Acetaminophen: more harm than good for chickenpox? J Pediatr. 1989:114(6):1045-1048.

- Graham NM, Burrell CJ, Douglas RM, Debelle P, Davies L. Adverse effects of aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen on immune function, viral shedding, and clinical status in rhinovirus-infected volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1990:162(6):1277-1282.

- Sugimura T, Fujimoto T, Motoyama H, et al. Risks of antipyretics in young children with fever due to infectious disease. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1994:36(4):375-378.

- Schulman CI, Namias N, Doherty J, et al. The effect of antipyretic therapy upon outcomes in critically ill patients: a randomized, prospective study. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2005:6(4):369-375.

- Prymula R, Siegrist CA, Chilbek R, et al. Effect of prophylactic paracetamol administration at time of vaccination on febrile reactions and antibody responses in children: two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009:374(9698):1339-1350.

- Li-Kim-Moy J, Wood N, Jones C, Macartney K, Booy R. Impact of fever and antipyretic use on influenza vaccine immune responses in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018:37(10):971-975.

Articles in this issue

about 5 years ago

NIH funds 8 new studies on COVID-19 related MIS-C in childrenover 5 years ago

COVID-19: It’s not the same-old same old!over 5 years ago

Newborn’s rash involves eyes and noseover 5 years ago

Itchy black spots: Poison ivy or something else?over 5 years ago

Ultrasound accurately diagnoses midgut volvulusover 5 years ago

Levonorgestrel IUDs are safe and effective in adolescentsNewsletter

Access practical, evidence-based guidance to support better care for our youngest patients. Join our email list for the latest clinical updates.