Diffuse targetoid and bullous skin lesions, mucositis, and ocular discharge in an adolescent male

Can you diagnose this adolescent with an 11-day history of diffuse targetoid and bullous lesions on his extremities and trunk?

Diffuse targetoid and bullous skin lesions, mucositis, and ocular discharge in an adolescent male | Image Credit: Author provided

The case

A boy aged 17 years presents with an 11-day history of diffuse targetoid and bullous lesions on his extremities and trunk, mucositis, and ocular discharge and crusting. The lesions are blistering and intensely painful.

What's the diagnosis?

Erythema multiforme (EM)

Epidemiology, clinical features, and etiology

EM is an acute mucocutaneous condition featuring red, papular, and often targetoid lesions on the extremities and trunk. There is also frequent involvement of the oral, ocular, and genital mucosa. Although previously considered to be on the same disease spectrum as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS, or bullous erythema multiforme) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), it is now accepted to be a distinct disorder. Pediatric EM more commonly affects male patients and can occur in children of all ages.1

Click to zoom

EM typically presents as erythematous target lesions and papules that may be pruritic or burn. The target lesions classically feature 3 concentric segments with a dark center surrounded by a lighter pink ring, then a darker red ring. Atypical lesions, with only 2 concentric rings, also are often present. Lesions may evolve over several days to become bullous. The lesions typically begin bilaterally on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and then spread proximally to the trunk. The lesions tend to be fewer on the trunk and face and have a predilection for areas of sunburn and physical trauma.2 Mucosal involvement features erosions on the lips, tongue, buccal mucosa, and, less commonly, the genital and ocular mucosa.1 Although the acute disease is usually self-limiting, it can also be recurrent or persistent in a small proportion of patients. Recurrent pediatric EM occurs more frequently in older children and male patients, with herpes simplex virus (HSV) being the most common trigger.3

Infectious agents or medications most often trigger EM. The most common infectious triggers are HSV and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, although other infections, including Epstein-Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus, group A Streptococcus, adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and COVID-19, have been reported. Drug triggers, including antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, also have been implicated. Finally, a small percentage of patients developed EM after vaccine administration, including the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine, recombinant hepatitis B vaccine, and the COVID-19 vaccine. EM is also idiopathic in many cases, although some cases with no identified trigger may be due to subclinical infection.3 If the trigger is not suspected, obtaining herpes simplex polymerase chain reaction test results from blisters and/or mucous membranes can rule out the most identified trigger.

Differential diagnosis

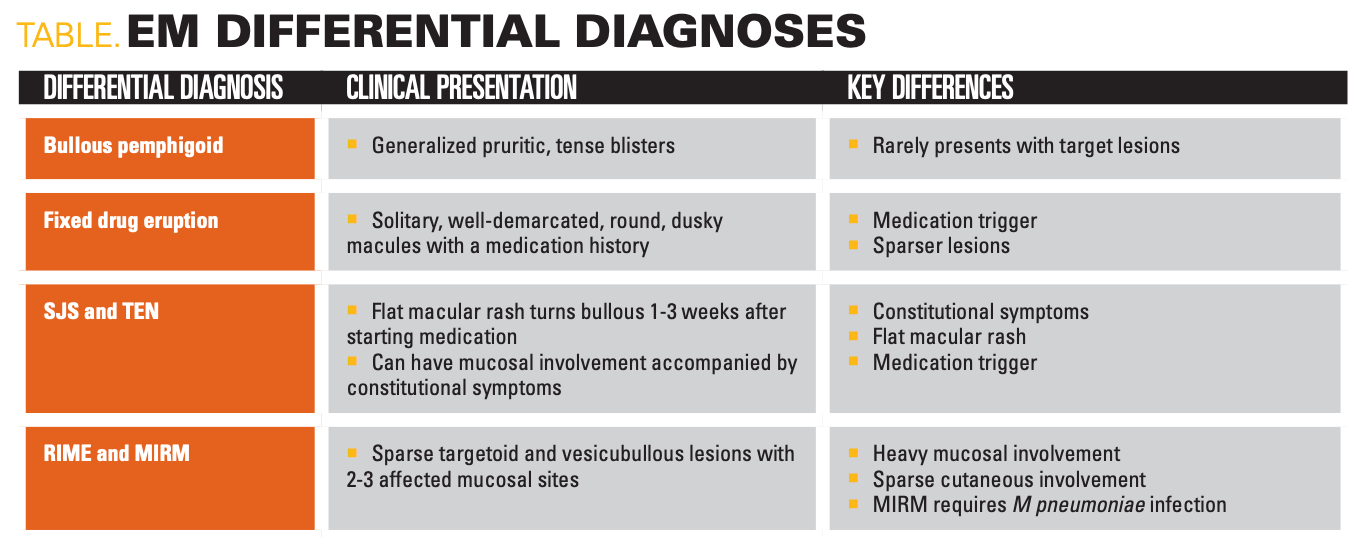

EM is diagnosed clinically, although a skin biopsy may help exclude other causes if the diagnosis is unclear (Table). EM may be confused with bullous pemphigoid or fixed drug eruption, although the distinct target lesions of EM help differentiate it.4 SJS and TEN may also present similarly, although they usually start with more purpuric macules that develop into blisters rather than papular, target-shaped lesions as in EM.5 Reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption and Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis are also in the differential, but can be differentiated based on distribution, as they usually present with sparse cutaneous lesions on the extremities and trunk but heavy involvement of several mucosal sites.6

Click to zoom

Treatment

If the etiology of EM is known, the offending infection should be treated or medication discontinued. Acute EM is managed with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines, with corticosteroid gel and oral anesthetic solutions recommended for mucosal involvement.7 Both HSV-associated and idiopathic recurrent EM are treated with antiviral prophylaxis, with the most effective regimen being continuous oral antiviral therapy for more than 6 months.8 For patients who are refractory to viral prophylaxis, adjuvant dapsone has elicited a partial or complete response in several case series.9 Immunosuppressants, including thalidomide, apremilast, and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), have also been shown in small case series to elicit complete or near-complete resolution of recurrent EM.10-12

Clinical course

Our patient had a history of recurrent erythema multiforme and was previously treated with daily valacyclovir with prednisone for flares. His flares progressively worsened, and his current flare was refractory to increased prednisone dosing. After consultation with dermatology, he initially received intravenous (IV) acyclovir, IV methylprednisolone, dexamethasone swish and spit, mupirocin ointment, triamcinolone ointment, and erythromycin ointment for his ocular involvement. For pain management, he received patient-controlled anesthesia hydromorphone with low-dose naloxone, methadone, gabapentin, ketamine infusion, and acetaminophen. A nasogastric tube was placed to maintain his nutritional status. Despite aggressive treatment of the condition, he experienced mild disease progression for several days, prompting further workup and consideration of other possible causes. A broad infectious workup was initiated, including an oral mucosal HSV/ varicella-zoster virus swab, respiratory viral panel, sexually transmitted infection panel, and mycoplasma and HSV1/2 antigen and antibodies. Only HSV1 IgG returned positive, not HSV1 IgM nor the HSV/VZV swab. Skin biopsy, however, was consistent with EM. After a week, MMF was added to the regimen, eliciting significant improvement in the patient’s condition. After 3 weeks of hospitalization, our patient was discharged on acyclovir and MMF with follow-up with his outside dermatologist.

References:

1. Heinze A, Tollefson M, Holland KE, Chiu YE. Characteristics of pediatric recurrent erythema multiforme. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(1):97-103. doi:10.1111/pde.13357

2. Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(8):889-902. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05348.x

3. Zoghaib S, Kechichian E, Souaid K, Soutou B, Helou J, Tomb R. Triggers, clinical manifestations, and management of pediatric erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(3):813-822. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.057

4. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(2):82-88.

5. Newkirk RE, Fomin DA, Braden MM. Erythema multiforme versus Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: subtle difference in presentation, major difference in management. Mil Med. 2020;185(9-10):e1847-e1850. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa029

6. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, Shinkai K. Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(2):239-245. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

7. Soares A, Sokumbi O. Recent updates in the treatment of erythema multiforme. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(9):921. doi:10.3390/medicina57090921

8. Tatnall FM, Schofield JK, Leigh IM. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of continuous acyclovir therapy in recurrent erythema multiforme. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(2):267-270. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb05024.x

9. Oak ASW, Seminario‐Vidal L, Sami N. Treatment of antiviral‐resistant recurrent erythema multiforme with dapsone. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30(2). doi:10.1111/dth.12449

10. Dias de Oliveira NF, Miyamoto D, Maruta CW, Aoki V, Santi CG. Recurrent erythema multiforme: a therapeutic proposal for a chronic disease. J Dermatol. 2021;48(10):1569-1573. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16046

11. Davis MDP, Rogers RS 3rd, Pittelkow MR. Recurrent erythema multiforme/Stevens-Johnson syndrome: response to mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(12):1547-1550. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.12.1547

12. Chen T, Levitt J, Geller L. Apremilast for treatment of recurrent erythema multiforme. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23(1):13030/qt15s432gx.

Newsletter

Access practical, evidence-based guidance to support better care for our youngest patients. Join our email list for the latest clinical updates.

Recognize & Refer: Hemangiomas in pediatrics

July 17th 2019Contemporary Pediatrics sits down exclusively with Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD, a professor dermatology and pediatrics, to discuss the one key condition for which she believes community pediatricians should be especially aware-hemangiomas.

Andrew Alexis, MD, MPH, highlights positive lebrikizumab-lbkz data for atopic dermatitis

June 25th 2025Lebrikizumab demonstrated efficacy and safety in patients with skin of color and moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in the ADmirable trial. Trial investigator Andrew Alexis, MD, MPH, reacts.