The problem with patient portals (and how to resolve them)

How pediatricians can best manage electronic health records without compromising patient care.

The problem with patient portals (and how to resolve them) | Image Credit: © woravut - © woravut- stock.adobe.com.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, 94% of pediatricians use electronic health records (EHRs).1,2 Regrettably, EHRs in many ways negatively impact medical care. They increase the amount of time we spend documenting visits and reduce the number of patients we can see each day. Additionally, they are unwieldly to use and are a major factor contributing to physician burnout.3

A survey of pediatricians demonstrated that we spend an average of 3.4 hours per day documenting care, while another showed that the average total active time per encounter that pediatricians spent in the EHR was 16 minutes, with 12% of this time spent after hours. Most of the time for each encounter is spent reviewing the chart, documenting the encounter, and placing orders for medications, labs, x-rays, and referrals.4

Patient portals and the pandemic

Currently, approximately 90% of US health care systems and providers offer patients online portal access to their EHR data. The creation of portals was expedited by the 2016 21st Century Cures Act, which mandated full, rapid access to a patient’s test results, medication lists, referral information, and clinical notes, upon request.5,6

This act went into effect several years before the COVID-19 pandemic. As a consequence of the pandemic, patient access to medical offices was limited and many patients began using patient portals to communicate with their primary care providers. Now physicians and staff are overwhelmed by EHR tasks associated with skyrocketing use (and abuse) of patient portals. In my own experience, in addition to documenting patient visits, I now need to deal with dozens upon dozens of patient requests for medication refills, referrals, explanation of lab results, and medical questions. Most pediatric practices don’t have the staff and time to resolve all these tasks in a reasonable time frame.

Here are some suggestions that can reduce the burden imposed by patient portals.

Expedite documentation

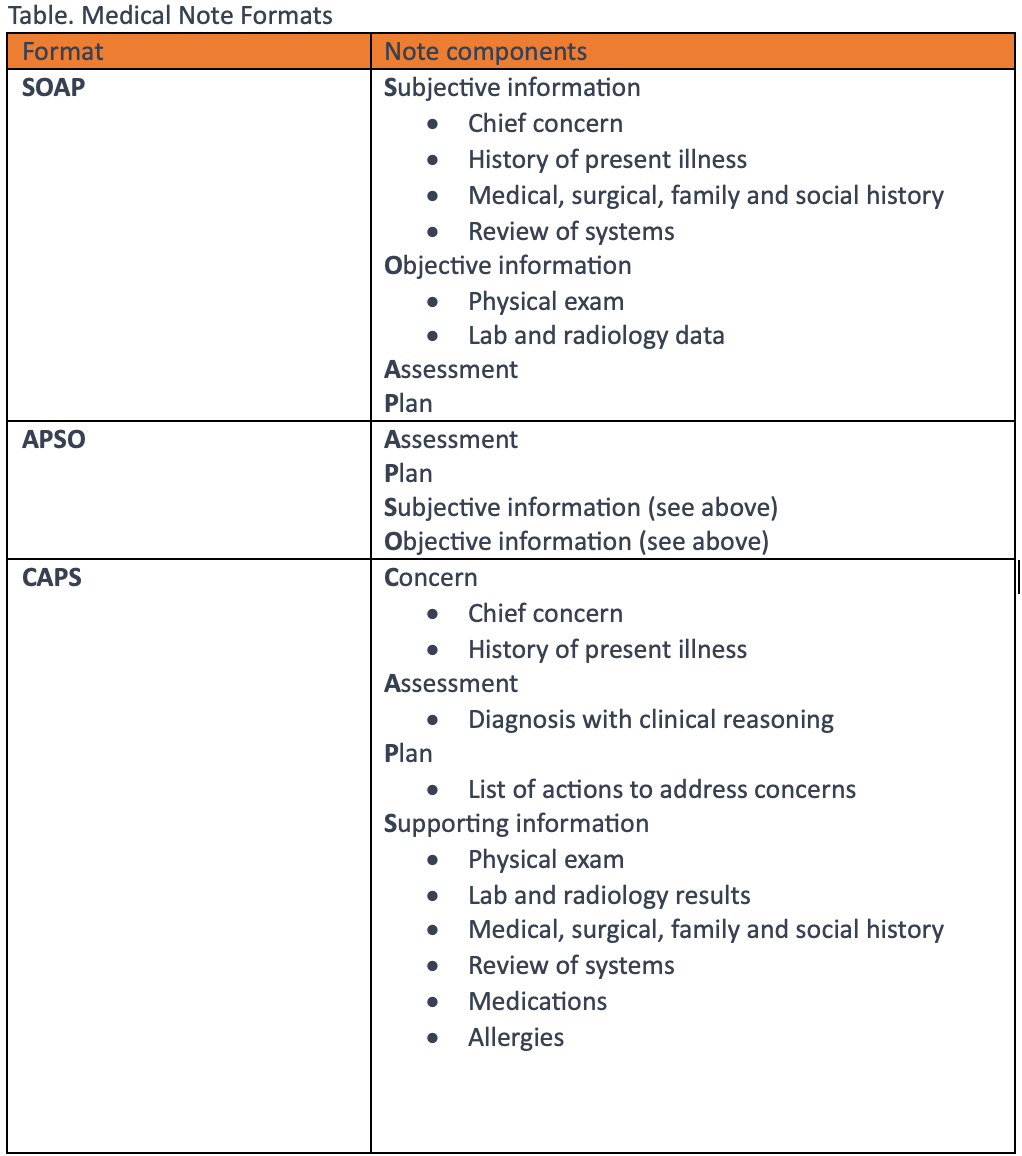

One way of dealing with our growing task burden is simply expediting note completion so that we have more time to devote to tasks. Notes do not need to be bloated but need to document all elements that justify the level of service provided for the visit and are adequate to provide continuity of care. As a courtesy to providers who must review your note prior to the patient’s next visit, consider using an alternative note format such as an APSO (assessment, plan subjective, objective) note or CAPS (concern, assessment, plan, supporting data) note (Table), which places the assessment and plan at or near the top of the note. These note formats facilitate care handoffs between providers, as a provider unfamiliar with a patient can easily determine the status of the patient’s problem. Also consider using either scribes or a digital scribe service to expedite documentation. Most providers can quickly learn to use Dragon Medical One to dictate into the EHR. As we can dictate accurately 3 times faster than we can type, notes can be completed quickly.

Pathways to task reduction

Communication with patients is a 2-way exchange and with some thoughtful planning, practices can reduce the number of daily tasks. With most patient portals, incoming patient messages are screened by nursing staff before they are sent to providers with questions regarding medication changes or medication refills. To reduce a physician’s task burden, support staff can prepare prescriptions and referrals for physicians so the physician can just review and sign the order. Because this still requires precious time each day in button clicking, 1 easy solution can be to establish standing orders that can be resolved through nursing intervention alone. Examples are an uncomplicated eye discharge or prescribing a prophylactic antibiotic following discovery of an engorged tick in a community where Lyme disease is prevalent. In these situations, physician involvement is not required.

This intervention, however, depends on the board of nursing in your state so it would be wise to check state regulations to see whether your nursing staff can use standing orders.

Because scheduling office visits is typically included in a patient portal, make sure patients can request visits but not schedule them. This prevents patients from scheduling very complicated visits in the last visit slot of your day. While we wish to do well by all patients, no one appreciates staying after hours to resolve complicated issues. This situation is often made worse if patients arrive late for their end-of-day visits.

Make sure the patient portal incorporates message filters so appropriate staff members are assigned incoming tasks. As an example, secretaries should receive scheduling questions and billers should get billing questions, while clinical questions should be screened by nursing staff before being passed on to providers.

The patient portal should incorporate links to a good medical information resource such as the American Academy of Pediatrics’ HealthyChildren.org so questions can be resolved by visiting the website rather than messaging the practice. Additionally, as patients enter the practice, parents should be given a letter explaining when portals should and should not be used. Also, consider integrating a version of the app Pediatric SymptomMD from Self Care Decisions LLC on your practice’s website or on the portal and encourage its use. This will markedly reduce the number of tasks a practice receives each day. Pediatric SymptomMD provides OTC medication dosages and answers routine questions.

Substitutes to patient portals

If you don’t feel your patient portal is as efficient as it could be, consider using an alternative. Subscription-based portals such as SimplePractice or DoctorConnect are Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant and facilitate communication with patients, preventing staff members from being overwhelmed. Via these portals, staff can schedule secure messages to remind patients of upcoming appointments and send patient forms for review and signature. Both integrate a telehealth application and are very affordable.

Turn tasks into visits

We often receive very complex task requests from patients that would be too time-consuming for an adequate response. The best way to deal with these situations is to schedule the patient for a same day or future visit. Alternatively, if your schedule permits, you can do an ad hoc televisit so you can visualize the patient and resolve the problem. In many situations, children with severe or worsening illnesses need to be sent to emergency rooms. Turning tasks into visits is good practice because it quickly resolves problems while generating revenue, while responding to tasks does not.

When all else fails

Long before we used EHRs, practices were very efficient in meeting the needs of patients. Requests typically came via the phone. Support staff would simply speak with providers about medication refills, referrals, etc. Sticky notes were everyone’s best friend. We documented in paper charts and we saw many more patients each day than we do now. In many ways, rather than using our EHR to communicate with staff, we should revert to speaking with staff directly or using the sticky notes communication system.

References:

1. Lehmann CU, O'Connor KG, Shorte VA, Johnson TD. Use of electronic health record systems by office-based pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e7-e15. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1115

2. Temple MW, Sisk B, Krams LA, Schneider JH, Kirkendall ES, Lehmann CU. Trends in use of electronic health records in pediatric office settings. J Pediatr. 2019;206:164–171.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.10.1039

3. Overhage JM, Johnson KB. Pediatrician electronic health record time use for outpatient encounters. Pediatrics. 2020;146(6):e20194017. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-4017

4. Schuman A. The great resignation: survival strategies for pediatric practice. Contemporary Pediatrics®. April 12, 2023. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://www.contemporarypediatrics.com/view/the-great-resignation-survival-strategies-for-pediatric-practice

5. Health information technology: HHS should assess the effectiveness of its efforts to enhance patient access to and use of electronic health information. US Government Accountability Office. March 15, 2017. Accessed August 10, 2023. www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-305?utm_source=blog

6. Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):501-504. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1006114

Newsletter

Access practical, evidence-based guidance to support better care for our youngest patients. Join our email list for the latest clinical updates.